Years of neglect are eroding gaming history. Cartridges rot in garages, companies hoard demos that they will never release, and obscure titles fade into the ether. Some games may even be lost forever.

What is happening?

The biggest threat to game preservation is the degradation of physical media.

Over time, game data and features literally die. Solid state media used in game cartridges naturally lose their electrical charge, and the ability to store any data. You might love Pokemon Gold and Silver but the internal battery on those carts only lasts about around fifteen years, maximum. You might boot it up to find that the in-game clock no longer works or that your save data is gone. Those are minor cases of lost data. EPROMs also carry essential data and code. Eventually, many games will be unplayable.

This piece originally appeared 12/2/16.

Magnetic media such as floppy discs and hard disc drives lose their orientation over time, eventually erasing the contents. Games and programming experiments from the medium’s early days are at risk of loss as their storage withers away.

“Time isn’t on our side,” archivist Andrew Borman said. Borman is a games historian who specializes in unfinished titles, recently discovering a canceled prototype for a Diddy Kong Racing sequel earlier this month. Borman notes that even recent media is degrading: DVDs and CDs from the mid nineties are at risk of decay.

“If we wait too long, there won’t be anything left to preserve.”

Forgotten floppy discs or prototype carts hold important game history. Their data tells us how games were made and who made them. Old games go forgotten and unplayed, giving a less complete idea of a console’s library or a genre’s progression. This media is disappearing due to improper storage. It’s not enough to keep our old games in a box at the back of the garage. Exposed circuit boards and EPROMs are damaged by dust and bright light. Humidity eats away at magnetic media. While some popular ROM sites and fan collectors copy data directly, such practices don’t necessarily ensure proper preservation of original games.

“I can’t guarantee that the person who copied a disc didn’t accidentally mess up something that changes the game,” Frank Cifaldi stressed.

Cifaldi is a games historian who helped Digital Eclipse release the Mega Man Legacy Collection. To stress the dangers of copying games, he points to The Oregon Trail. That title keeps track of save data to write names on tombstones the player encounters in their travels. The popularly available version likely has different data than the original, creating different tombstones.

This may seem like a small thing, but it’s the difference between a one hundred percent re-creation and an imperfect copy. The potential of lost source data or imperfect copies causes very real anxiety for archivists who want to preserve the genuine article.

Frank Cifaldi spoke about the problem at this year’s GDC.

What are we losing?

Consider the ill-fated Nintendo 64 version of Mother 3. While the Gameboy Advance version was successfully released in 2006, a demo of the Nintendo 64 prototype was playable in Japan at the 1999 Nintendo Space World Convention. There’s been no other playable version since and no copy of this build has been recovered.

“That’s an example of a historically significant work,” Cifaldi said. “It could tell us a lot about the process that went into a game we consider a masterpiece but it’s probably lost forever.”

Mother 3 highlights the difficulties of bringing commercially released games to a global audience. It has never been officially released outside of Japan. To play the game, fans must download a ROM file as well as the fan translation patch that was completed in 2008. Pirates and hackers are responsible for bringing that game to a wider audience, not Nintendo.

Above: some of the only footage from the Nintendo 64 version of Mother 3

One of the gravest examples of this is the original version of Final Fantasy 7. Work began on that game as early as 1994 when it was intended to be a Super Nintendo title. It was possibly going to take place in modern New York. An image of the game can be found in the Final Fantasy 25th Anniversary Ultimania memorial books. It is some of the only material proof that the project existed.

Test builds and materials for that game could offer important insights about one of the gaming’s most cherished titles. That history is largely lost; most people only know about the version of Final Fantasy 7 that was actually released.

“Developers throw things out constantly,” Borman commented. “Years of work are lost after projects are canceled.”

Why aren’t more people helping?

Jason Scott works for the Internet Archive, popular for their Wayback Machine, which hosts thousands of old computer games in their ongoing effort to catalog the internet. He gave a talk about preservation at GDC 2015.

“I have zero faith in the industry to preserve its own history,” Scott told me.

“The best I could hope for is a somewhat lax attitude at others doing it for them, and providing things when asked.”

The problem is not necessarily a malicious one: the legalities of sharing old prototypes and unreleased games can prove problematic, because they often contain proprietary secrets. Employees are bound by non-disclosure agreements that promise harsh legal action if games or associated materials are leaked to the public.

Some developers do buck the trend, though. Early this year, Volition released a cancelled Saints Row project to the public. This type of action is a rarity from an industry that values secrets.

Some of this is a cultural problem. Gaming’s early years often painted video games as children’s toys. Only diehard collectors and enthusiasts had the foresight to hold onto their games. Even now, games are treated largely as consumable goods. We look forward to the next big release. Publishers hype up sequels and new IPs. The gaming press is often beholden to topicality to draw in readers. Our culture is forward facing. We hold on to less and less of our past and are often incentivized to forget about it, because a better game can be pre-ordered for the future. Fans and gamers often discard older games or trade them in for quick cash at GameStop or pawn stores.

The problem of preservation extends beyond actual games—the culture itself is in jeopardy. Magazines, guidebooks, reviews, and merchandise help us understand a game’s impact, but these materials are also being lost as well.

“What I think we’re in the most danger of losing right now is context,” Cifaldi said. “I think we’re in danger of losing the history around these games as opposed to losing the ability to launch and play them.”

The fight to protect games is made even messier due to a lack of strict support from major developers. The Entertainment Software Association is an organization dedicated to the interest of game makers and publishers. Last year, they attempted to persuade the US Copyright Office to crack down on the preservation efforts of museums, claiming that the process involved illegal hacking. A major organization dedicated to “serving the business and public affairs needs of companies” actively tried to hamper legal preservation. Only the non-profit Electronic Frontier Foundation pushed back.

As a result of this lack of industry support, a loose network of archivists and hobbyists have stepped up to restore and preserve history wherever they can find it.

Matthew Callis is a hobby preservationist who maintains a catalog of Super Nintendo games at superfamicom.org. Recently, he helped coordinate an effort to win four long lost Kirby games from an auction in Japan’s Ishikawa Prefecture. He told me it can be difficult to get games out of the hands of possessive auctioneers and merchants.

Shady collectors are known to hold onto the only copies of rare games because it helps increase the value of a game. Those lost Kirby games that Callis and his colleagues found at auction? Someone actually has the rest of them and refuses to share the data on the internet. Such greed often hampers the effort of preservationists.

Callis and his peers had to resort to crowdfunding to buy the few Kirby games that they encountered. It was a gesture of greater interest from fans that shows one path forward in the battle to save games. A broader cultural interest in preservation will only make it easier to get games in the hands of people who will actually share them. It also means that the hard work spent on making these games was not in vain. Historians get to learn about the medium, developers get to have people play forgotten games, and fans get to enjoy new experiences. Everyone wins.

Archivists encourage employees and workers to take a particularly active role in preserving media, even if it means dramatic action.

“Workplace theft is the future of game history,” Jason Scott said during his talk at GDC 2015. It’s a sentiment shared by other preservationists.

“As an archivist and historian, I don’t think I can be respectful of intellectual property,” Cifaldi said. “I think that goes against my work.”

The means for sharing and playing old games fall into a legal grey area. Emulators can help, and are readily available online, but they are treated like illicit software. Major companies spread the myth that emulation is illegal. Nintendo, for instance, has an FAQ page that places emulation on par with crimes like counterfeiting.

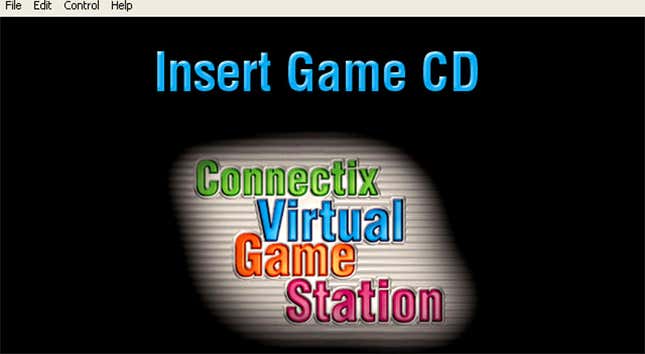

This is misleading: emulators have never been ruled as illegal in any court of law, as proven by a 2000 court case between Sony Entertainment and Connectix Corporation. Connectix produced a commercial Playstation emulator called the Virtual Game Station. It was concluded to be a transformative work, as the court acknowledged it used Sony’s original hardware in a new and unexpected way. Connectix’s copying of Sony programs and fireware was also determined to be fair use, as it was essential in creating the emulator. The VGS and other emulators fall completely within the bounds of the law.

It is also legal to keep copies of software for certain purposes, as outlined by the United States copyright law. 17 U.S. Code § 117 states that it is legal to copy and keep software for “archival purposes.” I personally maintain a collection of disc images, downloadable save data, and promotional materials for the Dreamcast title Skies of Arcadia explicitly for that reason. That collection is slowly expanding to cover more and more Dreamcast materials.

How can I help?

It’s easy for fans to get involved in protecting games. It’s also far less illicit than game companies claim. This is crucial because increasing the scope of archiving and collection is an essential step to preserving our history. It also keeps games out of the hands of those who only seek to exploit their value for profit.

Additionally, fans can attempt to keep games alive in the public conscience. Streaming games, writing blog posts, having forum discussions, and working on fan creations all help keep the spirit of old games alive.

“Players and fans should capture gameplay videos and record their thoughts on playing games,” Scott suggested when asked what simple things could be done to help preserve games.

“There’s only so much that individuals can do,” Cifaldi commented. “I think we need to use our power to publish and share things can help create an oral history around games.”

Callis sums it up more succinctly. “If you care at all, make an effort.”