Well, friends. We’ve come to the end of the road, at least for now. Episode nine of HBO’s The Last of Us is the season finale, bringing us to the end of the story told in the first game. Even the episode’s title, “Look for the Light,” neatly closes the loop opened by that of the first episode, “When You’re Lost In the Darkness.” Deeply faithful to the game’s provocative, morally ambiguous ending and other famous story beats in its final chapter, the episode nonetheless departs from the source material in a few key ways, starting with its opening. Let’s start with the beginning of the end.

Ashley Johnson as Ellie’s mother Anna

Notably, this is the first entry since episode two that begins with a cold-open prologue rather than the title sequence. After the first two episodes, I actually thought this was something the show might be committed to in the long term, with each episode kicking off with a different, relevant glimpse of life before the pandemic or some other thread that could inform our understanding of what was to come. But no, the device fell away early on, only to make one last return for the season finale, with a flashback that doesn’t exist in the game and that gives us a new perspective on two key characters: Marlene, and Anna, Ellie’s mother.

A few days ago, Neil Druckmann, co-creator of the game The Last of Us and one of the showrunners of HBO’s prediction, tweeted this:

The image here is not a reference to a real thing that exists in our world. Rather, it’s a fictional comic book referenced in Uncharted 4, the final game in Naughty Dog’s other big franchise of the past 15+ years. But it speaks to the idea that Anna, Ellie’s mother, is a character who the writers of the game (and now the show) have thought a lot about, even if, until now, she’s never actually been seen. Players of the game will know that she and Marlene were friends, that Marlene promised Anna she’d look after Ellie, and that Anna was alongside Marlene in the fight for a better world, but this is her first actual appearance in official The Last of Us media, and the actor playing her is none other than Ashley Johnson, who plays Ellie in the games.

We see Anna running through a forest, pursued by shrieking infected. As if that weren’t tough enough, she’s pregnant and going into labor. She emerges into a vast clearing dominated by a farmhouse, the Firefly insignia emblazoned on the nearby grain silo.

Racing to the top of the house, Anna barricades the door with a chair and draws a familiar-looking switchblade. Tragically, the determined infected busts through, and though Anna plunges the switchblade into its neck, it’s not before she’s bitten, sealing her fate. Ellie is born, and Anna cuts the umbilical cord. It must be something about the timing of all this that resulted in Ellie’s immunity.

Anna takes a moment to bond with her daughter, as we watch, knowing she has a few hours at best to spend with the child. And the credits roll.

Marlene and Anna

Night falls, and three lights cut through the darkness, a possible visual nod to the Firefly slogan. Marlene and two men find Anna still in that room, quietly singing to baby Ellie. The song she’s singing is “The Sun Always Shines On T.V.” by A-ha. It’s a song we know Ellie hears later in life, as she has a cassette tape of A-ha’s greatest hits in episode seven, which makes use of the band’s “Take On Me” at one point. (Interestingly, though “Take On Me” was a bigger hit in the U.S., “The Sun Always Shines On T.V.” outperformed it in the UK.)

Marlene immediately sees the bite on Anna’s leg, and here’s where something extraordinary happens: Anna says she cut Ellie’s umbilical cord before she was bitten. Of course it’s perfectly understandable. She did cut it only moments after, and whatever survival instinct she may have once had for herself has likely now transferred onto her daughter. She wants to give her daughter a chance. But as a thematic device, it’s significant because it bookends this final episode with lies. Ellie’s life begins with a lie, and later, it’s changed by one, both from people who, in their own ways and for their own reasons, are very invested in keeping her alive.

Anna, reminding Marlene that they’ve been friends for their whole lives, tells Marlene to kill her and to take care of Ellie, and to give her the switchblade. Marlene protests that she can’t, she can’t do any of those things, she especially can’t kill her friend, but then she musters the strength to do so. She is no stranger to gritting her teeth and doing what must be done in the struggle for a better world. You can tell it eats her up inside, but the world of The Last of Us offers little alternative for one who is truly, deeply committed to making a difference.

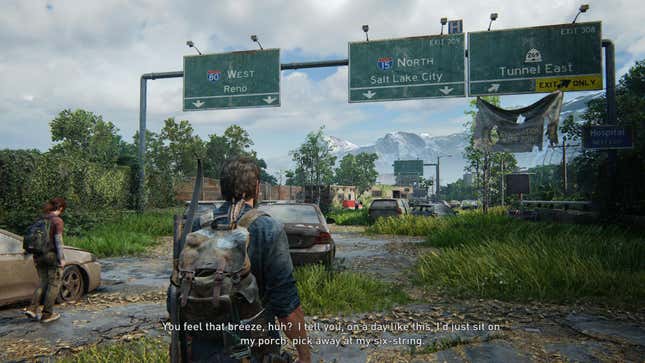

Salt Lake City

Now the show leaps into its approximation of the game’s final chapter. In both, Joel is uncharacteristically chatty, his bond with Ellie no longer in doubt after all they’ve been through together and especially after the harrowing events of episode eight. Ellie, by contrast, is preoccupied, remote, distracted perhaps by the magnitude of what their arrival in Salt Lake City could mean. While the Joel of the game talks about what a beautiful day it is, TV Joel excitedly shows Ellie that he found a can of Chef Boyardee, calling back to their campfire meal in episode four when the good chef’s awesomeness was one of the few things they could agree on. Both Joels talk about one day teaching Ellie guitar, and though she says she’d like that, it’s clear that right now, she has other things on her mind.

One interesting detail from the game that’s omitted from the show is a dream that Ellie tells Joel about, in which she’s on a plane and it’s going down, so she busts into the cabin only to find that there’s no captain. So she takes the controls but she doesn’t know what she’s doing, and just as the plane is about to crash, she wakes up. It’s a pretty typical anxiety dream—I actually have nightmares about plane crashes from time to time myself—and it makes sense that Ellie would feel that her life is out of control, but she remarks on the strangeness of having a dream set on a flying plane when she’s never flown on a plane in real life. She never got to experience the pre-cordyceps world, and yet the ghost of it is everywhere around her.

The famous giraffe scene

Joel and Ellie cut through a building on their way to the hospital, and in the show, for what I’m pretty sure is the first and only time, Joel does something he does repeatedly in the game: he boosts Ellie up, here so she can lower a ladder for him. However, the usually attentive Ellie is caught off guard by something and instead ends up just dropping the ladder and running off to look at something. Joel pursues her, perhaps worried at first that she’s in danger, and what follows is one of the game’s most famous moments, faithfully recreated in the show.

What he finds is Ellie, standing awestruck by the sight of a giraffe, peacefully munching on some leaves growing on the building. In the game, Joel encourages Ellie to pet the giraffe. In the show, he encourages her to grab some leaves and feed it a little bit, and the sight of its long tongue reaching out for that green goodness is pretty great. For Joel, though, the best sight here is the sight of Ellie enjoying this moment. You can tell, particularly in the show thanks to Pedro Pascal’s acting, that Joel is happy to be alive to witness and share in this moment with her. So often, it’s not the thing itself that matters, so much as it is the sharing of it with someone.

Read More: The Last Of Us Show Tries To Change What The Game Tells Us About Joel

Perhaps part of why we’re drawn to apocalypse stories is the way they can help us focus on what really matters. There’s a line in last year’s HBO post-apocalypse prestige drama Station Eleven (based on the novel by Emily St. Mandel) from central character Jeevan who says, “Having just one person, it’s a big deal. Just one other person.” I’m reminded of that in this scene. Like Station Eleven, The Last of Us is deeply concerned with what makes our lives mean something, and in my experience, that’s always tied up in connection with others, in one way or another.

Moving to another spot which lets them watch the whole giraffe family walk off into the distance, Joel asks Ellie a question he asked her much earlier in the game, or, in the case of the show, way back in episode two, as they stood looking toward the capitol building in Boston. “So, is it everything you hoped for?” Ellie recalls that moment too and says it’s had its ups and downs before repeating something she said back then as well: “You can’t deny that view.” It’s a moment that makes us feel the journey they’ve been on, all the ground they’ve covered, the time that’s passed, and all the ways in which things between them have changed from that moment so much earlier, when all Ellie was to Joel was some human cargo he resented having to deal with. Coming to this moment in the game again as I replayed it for this recap, knowing what was coming, I almost wanted to linger there forever, to let them linger there forever, and spare us all the pain ahead.

Now, he doesn’t want to imagine his life without her again, and so he tells her that she doesn’t have to go through with this. In both the game and the show, her response is the same: “After all we’ve been through, everything that I’ve done, it can’t be for nothing.” She tells him that once this is done, they can go wherever he wants, but “there’s no halfway with this.” In the game, Joel looks up just in time to see the last giraffe disappear into the distance. The moment has passed. Their choice is made.

Joel tells Ellie the truth

Next, their journey to the hospital takes them through a triage camp the army set up in the days immediately following the outbreak. In both the game and the show, this is the site for a confrontation of sorts with Joel’s past, though that takes very different forms in each version.

In the game, Joel mentions having been in a similar camp after the outbreak. When Ellie asks if it was after he lost Sarah, he says yes, and she tells him how sorry she is for his loss. Previously, Joel’s forbidden Ellie from mentioning any of his losses, from talking about Tess or his daughter, but this time, he says “That’s okay, Ellie.” A short time later, Ellie gives Joel the same photograph of himself with Sarah that he refused earlier when Tommy offered it to him. Ellie says Maria showed it to her back at the dam and she stole it. Joel, obviously moved, says, “Well, no matter how hard you try, I guess you can’t escape your past. Thank you.”

In the show, however, we return to something first teased back in episode three. At the time, Joel said that the scar on his forehead was from someone shooting at him and missing. Now, he tells Ellie that the wound is what landed him in triage, and also that “I was the guy that shot and missed.” After Sarah’s death, he “couldn’t see the point anymore,” he says, but he flinched when he pulled the trigger. “So time heals all wounds, I guess?” Ellie asks. Joel says “It wasn’t time that did it” and gives her a meaningful look.

After this emotionally heavy moment, Joel seeks to lighten things up by actually requesting some shitty puns. It’s a great little exchange, with Joel and Ellie disagreeing on the quality of some of the jokes—one she declares “actually good” and he calls “a zero out of ten”—but my favorite bit is when Ellie says “People are making apocalypse jokes like there’s no tomorrow.” Joel at first looks scandalized but when Ellie asks, “Too soon?” Joel says, “No, it’s topical.” Joke time is soon interrupted, though, when some kind of gas grenade gets tossed their way, Ellie is dragged off, and Joel is conked on the head with a rifle.

One last dance with infected before all is said and done

This episode and its differences from the game’s corresponding sequence reveal some interesting differences in how the game and the show approach pacing and combat. In the show, episode eight was the final crucible, the peril and terror of that situation solidifying Joel and Ellie’s bond, and it likely would have been anticlimactic for the two to have another encounter with infected at this point. The dramatic purpose of such encounters has already been fulfilled. There’s really nowhere else for them to go. In the game, however, as a mainstream commercial product released in 2013, it would have been strange for there not to be one final encounter with infected. For many players, such combat is first and foremost what they come to a game like this for. So you do have one final encounter with a whole mess of infected (including multiple bloaters) in the partially flooded tunnels near the hospital. Once they’re all finished off, Joel utters Ellie’s favorite catchphrase, “Endure and survive.”

They’re not out of the woods yet, though. A bit later, Joel gets stuck in a bus that’s rapidly filling with water. Ellie (who can’t swim) attempts to rescue him, but is herself swept away. The current carries Joel toward her and he sees her, framed by light, before pulling her up out of the water and attempting to resuscitate her. This is where the Fireflies find them, and knock Joel unconscious.

Marlene and morality

Joel wakes up in a room with Marlene (Merle Dandridge in both the game and the show), who marvels at the fact that the two of them came all this way and survived, that Joel actually managed to deliver Ellie there, when the same journey cost the lives of so many of her people. “It was (all) her,” Joel says. “She fought like hell to get here.”

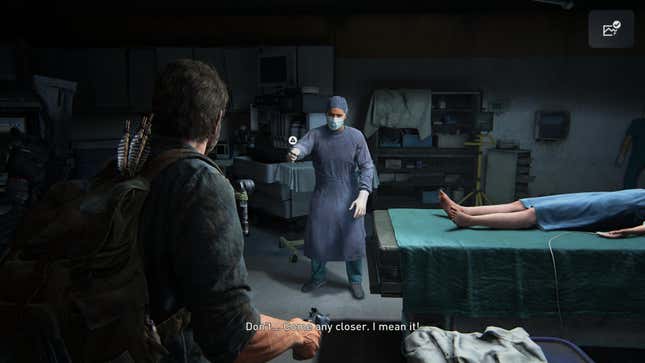

When Joel insists on seeing Ellie, Marlene tells him he can’t. “She’s being prepped for surgery.” When Joel realizes that cordyceps grows in the brain and that the surgery Marlene is describing means Ellie’s death, well, he knows what he has to do.

Notably, in the show, Marlene offers a more detailed explanation of Ellie’s immunity, and how the doctor intends to use that to create a cure. I suspect that this, along with Joel’s line back in episode six suggesting that if Marlene says they can make a cure, they can do it, are meant to deflect the fairly common response to the show’s central moral dilemma, a response I saw as recently as this past weekend on Twitter, that says “They probably wouldn’t have been able to make a cure anyway.”

My issue with this response is that I view it as a reluctance or refusal to engage with The Last of Us on its own terms. I think it’s a copout, a way to more easily justify what Joel does by saying “the stakes weren’t that big anyway” by disregarding the internal logic of the work itself. Sure, if you view The Last of Us in “realistic” terms, you can say that the odds of a vaccine being made weren’t great, but that’s not the moral dilemma we’re being asked to engage with here. The game and the show both work to establish this as a situation in which a vaccine is clearly possible.

The game does this in part through an audio diary you can find in the hospital in which the lead surgeon rattles off a bunch of whatever the medical equivalent of technobabble is, terms and phrases that are meant to sound legitimate within the fiction of the game and establish that the surgeon knows what he’s talking about. He then says, “We’re about to hit a milestone in human history equal to…the discovery of penicillin. After years of wandering in circles, we’re about to come home…All our sacrifices, and the hundreds of men and women who’ve bled for this cause, or worse, will not be in vain.” We are meant to view what Joel does as in opposition to that, as overriding all of that. That’s not to say that we can’t still conclude that Joel is right to do what he does. But we should at least consider it within the moral calculus that the game and the show actually establish.

Ten years ago, I felt that so many players’ reaction to the game’s climax was not just one of agreeing with Joel but one of cheering “Fuck yeah!” while he did what he does, of reveling in his undoing of everything the Fireflies have done, in his murder of Marlene, and I wonder if some of that isn’t just because it’s very easy to feel fully aligned with someone when you’ve spent so long walking in their shoes. But I can imagine a game focused on Marlene, one that follows her for years and years, from establishing the Fireflies, working with and then tragically losing Ellie’s mother Anna, watching over Ellie from afar while trying to undermine FEDRA and seeking a cure or some way to unfuck the world, all the while seeing her fellow passionate believers fight and die alongside her, and then coming to the heartbreaking moment where her own best friend’s daughter is the world’s last best hope. I wonder if, given the chance to experience Marlene’s struggle that way, to see things from her perspective, some people who see the ending of The Last of Us in very simple terms might find their view of it complicated.

And this was Anna’s fight as well. You can find an audio log that’s effectively Marlene speaking to Anna, to the memory of her friend, and in it she says “Here’s a chance to save us…all of us. This is what we were after…what you were after.” I don’t think any of this is at all easy for Marlene. I think she’s just learned by now how to do even the things she finds very, very hard, if she believes it supports the greater good.

None of this is simple. I’m conflicted about it myself, and I do sometimes put one life ahead of many. (It’s just a game, of course, but you’d better believe that at the end of Life Is Strange, I made the choice to save the one person I felt close to and cared about deeply over a town full of others.) And I have no problem with Joel doing what he does. As I’ve said before, I want art and media that depicts human beings doing questionable or complicated or awful things sometimes. I just want people to actually engage with that complexity, rather than acting as if feeling at all conflicted about how all this plays out is silly and that Joel does the only reasonable thing he could have done.

Saving Ellie, dooming the world

Marlene, sensing that Joel is gonna be a problem, tries to have him escorted out of the building. However, he kills his escort, and fights his way through the hospital to save Ellie. In the game, I find this sequence quite challenging. The hospital provides your Firefly enemies with so many opportunities to flank you. The Joel in the TV show seems to have it considerably easier. (And in case anyone is wondering, yes, in the game you do get a new weapon, the assault rifle, here, just like Joel does in the show.) In any case, he kills a whole mess of dudes on his way to Ellie.

Arriving in the operating room, Joel orders the doctor to unhook her. He grabs a scalpel and stands in Joel’s way. Joel kills him, too. Yes, the doctor was about to take her life. By doing this, though, Joel has taken the life of someone who was deeply loved by somebody else. And how many of the people he killed on his way up here will also leave a void in the lives of people after today? God, what a moral mess.

Joel has one last encounter before he makes his escape, this time with Marlene. In both the show and the game, Marlene asks Joel to consider what Ellie herself would want. The look that plays across his face in both cases shows that he knows what he’s doing isn’t what she’d want.

After years and years of working tirelessly for a shot like this at a better world, after sacrificing so much, Marlene, too, is killed. “You’d just come after her,” Joel says, before pulling the trigger.

Joel’s lie near Jackson

Ellie wakes up in the back of a car, still in her hospital gown. Joel’s driving them to Jackson, and when she asks him what happened, he feeds her a lie about there being dozens of people who share her immunity, and the doctors not being able to make any use of it all, to the point that “they’ve stopped looking for a cure.” Ellie is obviously crushed.

Significantly, in the game’s short final sequence, you play as Ellie as she and Joel walk the last bit of distance toward Jackson. Joel, ready for his life with Ellie to begin in earnest, starts talking about how much he thinks Sarah would have liked him. Ellie is, of course, preoccupied, and eventually she stops Joel, and starts talking about how she lost Riley.

The point of the story, I think, is that Ellie felt left behind (sorry) by Riley’s death, that she would have rather died if it could have meant a cure than being alive, and that she suspects Joel made a choice of his own accord to save her rather than let that happen. Joel, perhaps sensing where this is going, tries to offer some of his old-fashioned wisdom about how it can be tough to come to grips with surviving but you keep finding things to live for. But she demands a straight answer, asking him to swear that everything he said about the Fireflies is true. “I swear,” he says.

There’s a long pause. Is she doubting him? Deciding whether she can trust him? Debating telling him that he’s full of shit? Where would any of that leave her now, in this world where everything she thought she was living and fighting for has now evaporated into nothing?

“Okay,” she says.

Final thoughts

Playing through the game again alongside watching the series gave me a lot to think about. Perhaps most of all, I thought about how, just by virtue of being an interactive experience that’s set in perhaps the most lovingly rendered vision of the post-apocalypse ever created, the game The Last of Us is much more about the haunted world than the show is. Naughty Dog clearly approached designing the locations you pass through very thoughtfully. They didn’t just design some assets and then toss them together. Quite the opposite. For every house or apartment you enter, you can tell that Naughty Dog asked themselves questions like: Who lived here? What was their cultural background? What did they do for a living? Did they have any pets? Most of us probably know the sense of emptiness a person can leave behind when they die. Closets filled with clothes they’ll never wear again. A toothbrush in the bathroom. This is a world filled with that emptiness.

On the other hand, I appreciate that the television show found a few opportunities, here and there, to remind us that even in its world, love is possible, and by extension, lives of meaning are possible. The game, with its framing of Bill and Frank’s relationship, with the tragedy of Henry and Sam, leans so relentlessly into loss and tragedy, with little dramatic counterpoint to remind us what love in this world—any kind of love, the love between a man and his adopted daughter, for instance—can even look like. Of course episode three—the Bill and Frank episode—was the most radical instance of the show departing from the game to offer an image of love, but it wasn’t the only one. Marlon and Florence in episode six got so little screen time, but there, too, thanks to the two wonderful actors cast in those roles, we got a sense of a real, lived-in relationship, people being there for each other across decades.

All of this is to say that I appreciate that the creative team behind the HBO show approached this undertaking as an adaptation, not merely a retelling or recreation. Now the wait begins for the show’s next season, when I look forward to finding out how they continue to not just re-tell the exact same story we’ve already experienced, but adapt it for a new medium.