“Retinas are fried after cranking up brightness to see enemies.” That is the headline of a Reddit post submitted one month ago to the Call of Duty: Cold War subreddit. His plight is achingly familiar. “It’s literally so difficult to see enemies in this game,” they write. So they delved under the hood and obliterated the darkness, so purging all those cowardly snipers who’d been shooting them in the back. Now, claims the poster, they’ve given themselves optical damage; a worthy trade off for an improved K/D/A.

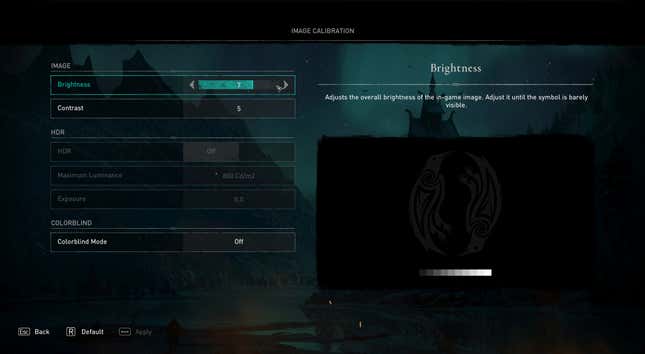

Personally, I have never destroyed my eyeballs with reckless graphics-settings malpractice, but I still absolutely sympathize with that poor Cold War gamer. Every month, I boot up a brand new video game and stare at a black screen embossed with the franchise insignia and a slider waiting for my input. You know the deal. “Slide the bar until the logo above is barely visible.” Okay, sure. The Assassin’s Creed seal is now blended deep into the inky darkness, ostensibly so I can experience Odyssey the way it was envisioned. The foamy churns of the Aegean sea shall be shrouded under the foreboding skies. The rolling knolls of the Greek countryside will taper off into the fading torchlight. The blood on the sand will resemble drops of oil under a full moon. Thank god for that brightness slider. I wouldn’t want to short-change myself.

And yet, inevitably, 20 minutes into the campaign I conclude that I can’t see shit, and that the slider is a junk mechanic conspiring against me. Back to the settings menu I go. The bar is now set firmly to the extreme right, and the logo in the void burns like a supernova. I’ve broken all the implied aesthetic rules set out by the game developer, and I couldn’t be happier. Never again do I bumble around in the murkiness of the underground catacombs, and those quest NPCs hiding out in the shadowy corners of the room are graciously revealed. I’ve experienced this so many times in my gaming career: Wolfenstein, The Elder Scrolls, The Witcher III, whatever. The brightness slider constantly lets me down. The presumed moody ambiance never manifests. Instead, at the beginning of most games, it feels like I’m simply being asked if I’m interested in seeing the levels or not.

I wanted to get to the bottom of this. The brightness slider has vexed me so many times, and I refuse to believe that I’m the only one with the problem. Surely, this is a feature that developers agonize over, right? They must understand how unreliable their built-in contrast dial is for millions of gamers. So, I ventured to the source of the discourse. Tim Willits is the former studio director at Id Software, and he’s responsible for one of the most oppressively dimly-lit games of all time: Doom 3. I brought my concerns to him, and he confirmed my worst fears: Yes, game-makers understand that “ideal brightness” is mostly bullshit.

“It is really difficult to make a game that looks the way you want it to look for everyone. The biggest problem we have is that we love to work in the dark. In the old Id days, we’d never turn the lights on. We’d have these really nice monitors. We’re trying to build a world that has atmosphere and a certain style to it, and [that] tends to make our levels really low-lit,” he says. “But few people play a game in the physical environment that you want them to play it in. They’ve got the lights on, they’ve got the window open. It doesn’t translate.”

Naturally, more than 15 years after its release, Willits happily admits that Doom 3 was lit in all the wrong ways, and the many players who complained about the constant alternation between the shotgun and the extremely radiant flashlight were right on the money. This was a miscalculation on many levels. As Willits explains, the Id team spent months, even years, mastering every wrinkle of the Doom 3 experience. They swore by the dark ennui, because by the nature of their jobs, they knew these maps like the back of their hands. Willits could probably make it through Doom 3 blindfolded if he wanted. But once the game is handed off to a hapless gamer, all of that dreariness is a lot more frustrating than it is mood-building. It is moments like that, after the fifth or sixth time you are obliterated by an imperceptible Cacodemon, that people tend to reach for the brightness settings to take matters back into their own hands.

There’s a technology issue at play here as well. All monitors are not created equally, which is an issue that becomes more apparent as our settings menus continue to swell with additional fidelity doodads. (Ray tracing! VSync! 4K! 8K!) It goes without saying that an Assassin’s Creed render is going to look different on a 15-year old Plasma than it will on, say, an iPhone 11 streaming gameplay off a Series X. That is a constant complication for developers. Alongside the cavernous vibes of most game studios, and the innate, speedrunner’s instinct they accrue as they flesh out the game world, a lot of those brightness sliders tend to hinge on whatever machinery the team is working with, which is rarely representative of the average consumer. “They should probably tell you that the game was developed on an ASUS ROG monitor or whatever,” laughs Timothy Ford, Assistant Technical Director on Overwatch.

Willits concurs: “Some people leave their TVs defaulted to what they’re supposed to look like at Best Buy. I just bought a new TV that adjusts automatically to the light, which I immediately turned off,” he says. “Every monitor is so different. As soon as your product hits the market, it’s the wild west.”

Of course, all the developers I spoke to for this story told me that, in the end, video game brightness is subjective. It may not seem that way when you’re forced to make a personal ascertainment of whatever “barely visible” means, but according to Willits, the people behind the engine don’t have a precise definition of that term either. “It’s abstract. I have people come up to me and say, ‘No, Doom 3 wasn’t too dark,’ which, they’re wrong about that,” he says. “To me, it just means, ‘How dark do you want your game to be?’ Personally, I crank up the slider a little bit. I want to see more of the game.”

Nina Freeman, veteran developer of games like Tacoma and a Twitch-partnered streamer, echoes that sentiment. She streams a lot of horror games on her Twitch channel, and tends to ignore the slider until she’s in the game and can sufficiently darken the surrounding geometry to her liking. That can be a point of contention with her fans. “It’s a difficult balance between my preference and my audience who’s like, ‘I can’t see!’”

So is there a more elegant solution on the horizon? Will society ever progress past the need for user-inputed brightness preferences? Willits doesn’t think so. There are too many variables and too many nonrepresentative truths in the way. For the foreseeable future, the slider, for all its faults, is what we’ve got.

“I wish I had something clever to say, but I think we’re stuck with it,” he finishes. “It’s a necessary evil that we just have to deal with. Because when technology tries to get too clever, it ends up being frustrating. I promise you, since 1995 when Id first started, we talked about this issue. Not much has changed.”

Luke Winkie is a writer and former pizza maker from San Diego, currently living in Brooklyn. In addition to Kotaku, he contributes to Vice, PC Gamer, Playboy, Rolling Stone, and Polygon.