“Faster, Faster, until the thrill of speed overcomes the fear of death.”

-Hunter S. Thompson

In much the same way that ancient peoples looked up at the night sky and imagined other worlds, the first video game developers looked at a thingy on a screen and imagined it moving really fast.

Who could blame them? Computers, since their inception, have been iterated upon with speed as a fundamental driving factor. Scour any historical rundown of the earliest computational devices and you’ll invariably discover some factoid about how a five-dollar Staples calculator can perform operations several orders of magnitude more efficiently (and it’s not even the size of a house!). Charles Babbage’s failure to complete the Analytical Engine was an implicit promise to his future understudies: some day, someone would complete it, and they’d make it better. Faster.

A century and a half later, they might even give it blast processing.

The early nineties marked a major inflection point for video games. 8 bits shot up to 16; color palettes entered the triple digits; Konami made a Simpsons beat-em-up. Once the fourth console generation was well underway, developers gradually shifted from revolution to refinement, trimming the fat from established design philosophies while doubling down on what already worked. Of course, increased processing power meant increased speed, and several of the era’s most acclaimed titles pointedly cranked up the velocity on their respective genres. Doom was a faster Wolfenstein 3D, Daytona USA was a faster OutRun, Chrono Trigger was a faster Dragon Quest, and—leading the vanguard in 1991—Sonic the Hedgehog was a faster Super Mario Bros.

Sonic—as a character, as a franchise—is a crystallization of video game hardware’s perpetual forward momentum. Here was a game created for the express purpose of literally outpacing the competition, a giant flashing “PICK ME” sign pointed at the Sega Genesis. It wasn’t marketed for its level design, and it didn’t need to be. Sonic was fast. He was named after fast. Level design doesn’t matter when you’re moving too quickly to see it. The novelty didn’t lie in the control itself, but in the notion that something so fast could be controlled at all.

At least, that’s what the commercials would have you believe. The first three mainline Sonic games (four, if you count Sonic & Knuckles as its own entry) drew audiences in with the promise of high-speed thrills, and then, with a wink, gave them physics homework. They were fast, but speed was a reward, not a guarantee. It could only be achieved via a combination of sharp reflexes and a thorough understanding of how Sonic responded to subtle changes in level geometry. Slopes, springs, and circular loops all affected his momentum in distinct ways, and oftentimes the quickest beeline through a level involved the most measured consideration of how to interact with it.

Nevertheless, the idea that Sonic was speed incarnate persisted. Maybe the marketing worked too well, or maybe people sensed, buried within this design, the possibility for something even faster. Why slow down at all? This is what computers are for. Hell, this is what life is for. Constant acceleration, wind whipping through your hair, pavement screaming past your feet. It’s why people become F1 drivers, and it’s why they play Sonic the Hedgehog. So let’s cut the crap. We’re all adrenaline junkies here. Juice that speed dial until it bursts into flames.

Over the course of the following two decades, this line of thinking metastasized into Sonic’s current design ethos: playable theme park rides that let players immediately go full throttle at any time with a press of the “boost button.” Boosting—which also turns Sonic into a moving hitbox, automatically razing most obstacles in his path—tickles the same part of the brain that likes watching sped-up GoPro videos, and not for nothing. It’s a visceral, inborn thrill, one that the best modern Sonic levels make compelling use of. Yet somewhere along the way, the friction vanished. Geometry stopped resisting player input in ways that encouraged creative play. Speed was no longer something to work towards, but something given freely. If Sonic the Hedgehog was about trick-or-treating, Sonic Unleashed and its progeny are about buying a discounted bag of mixed candy on November 1st.

But there exists between these two approaches an exact midpoint. A game that made good on the franchise’s dual promises of high speed and deep skill, blending the two so seamlessly and emphasizing them so severely that its innovation is overshadowed by its lucidity. Of course Sonic should be like this. Why was it ever not? Why isn’t it now?

Sonic Advance 2 was first released in Japan on December 19, 2002, for the Game Boy Advance. It’s the perfect Sonic game, and maybe, by extension, the perfect video game. It refined all of its predecessors and influenced all of its successors, yet it remains the only installment of its exact kind, a 2D side-scroller released in the midst of Sonic’s uneven transition to 3D and met largely with subdued praise. In hindsight, we should have been louder. This was as good as it would ever get.

Developed as a collaboration between Sonic Team and then-nascent studio Dimps, Advance 2 followed up 2001’s more traditionally-designed Sonic Advance; in 2004, it would receive a sequel in Sonic Advance 3, which capped off the sub-series. As with most of the classic Genesis games, Advance 2 features seven zones, each with two “acts” and a boss battle. There are five playable characters, a gracious but altogether empty gesture. Always pick Sonic. He’s the fastest one.

This is the first Sonic game that I’d feel comfortable describing as “being about speed” (though I wouldn’t go so far as to say it’s all about speed, because if it was all about speed, it wouldn’t be about anything else). Characters are exponentially faster than they’ve ever been. The difference between how they control in Advance 2 versus Advance, let alone the original trilogy, is staggering, as though the development team was hit with a sudden, explosive realization that they had the tools at their disposal to finally make the game people had been expecting (consciously or otherwise) for over a decade. And then they took it a step further. They wondered what would happen if, after speeding up, you never had to slow back down.

Enter “boost mode,” Advance 2’s load-bearing mechanic. It works like this. First, start running. Then, keep running until you hit top speed. (Rings, the series’ longstanding collectible currency, now act as more than just a damage buffer–the more you have, the faster you accelerate.) Finally, maintain top speed for long enough and the tension will snap: you’ll enter a unique state, visually indicated by what appears to be the sound barrier shattering, in which your speed cap is raised even further, allowing you to airily zip through stages almost too quickly for the screen to keep up. As long as forward momentum is sustained, so is boost mode; stop too suddenly or take damage and you’ll need to work your way back up. The flow of this design—wherein a sort of zen-like mastery over one’s environment is achieved through intense focus—is not unlike meditation. Advance 2 understands that boost mode can’t be free, because meditation isn’t easy. If everyone could meditate, nobody would argue about video games anymore, and I’d be out of a job.

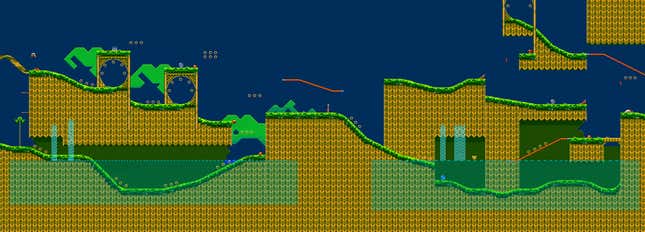

The game’s stages, which have been expanded in size by a factor of six to accommodate higher speeds, fluctuate accordingly. Levels will feature long, relatively uncluttered stretches of flat or sloping terrain that might barely give players enough room to activate boost mode, followed by more precise platforming segments that challenge them to keep it. The majority of these segments are meticulously designed to allow momentum to carry over between jumps, so long as one’s understanding of Advance 2’s movement is sufficiently honed. And that movement, even disregarding boost mode, is astonishingly complex.

It’s worth noting that Dimps was founded by Takashi Nishiyama and Hiroshi Matsumoto, two fighting game alums whose greatest claim to fame was their co-creation of Street Fighter; they were also involved in varying capacities with Fatal Fury, Art of Fighting, and SNK vs. Capcom, among others. It’s a God-given miracle that these guys—who may understand video game movement better than anyone else on Earth—not only decided to take a crack at Sonic, but more or less perfected it on their second try.

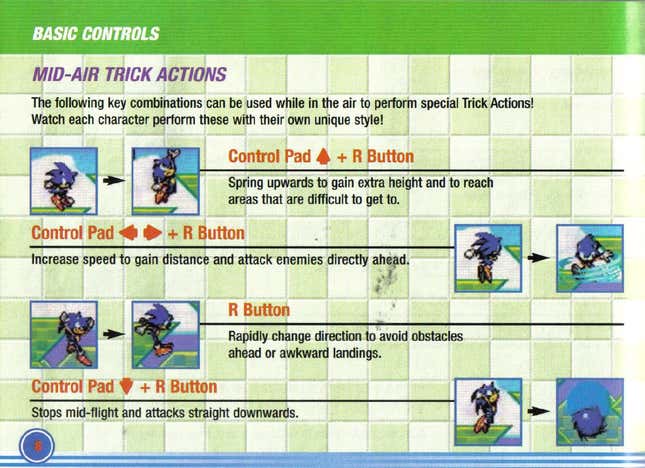

Advance 2, put simply, has options. Each character comes equipped with multiple unique grounded moves, aerial moves, boost mode-exclusive moves (useful for clearing away enemies that would otherwise knock your speed (and rings) back down to zero), and, most ingeniously, aerial “tricks” that propel them along set trajectories when used in certain contexts. Mastering Advance 2 means intuiting exactly which tricks will strike the best balance between progression, momentum, and evasion, the goal being to bypass as much of the stage as possible without ever slowing down.

And then there’s Sonic, the sole character with an air dash, which can be executed by double-tapping forward in midair (an input immediately recognizable to anyone with even cursory knowledge of fighting games). To me, this move—the only one not mentioned in the game’s instruction manual—is proof positive that Advance 2’s designers thought of speedrunning as a feature, not a bug. Its execution is just difficult enough to appeal to higher levels of play, but not so difficult as to feel unreasonable. The result, once all of these options are successfully melded, is poetry in motion, a hypnotic string of lightning-fast jumps, flips, dashes, spins, and sprints. Advance 2 speedruns are all the convincing I need that Sonic never had to enter the third dimension: everything the series ever needed is right here, in this tiny, unassuming, 4.3 megabyte GBA cartridge.

In fact, if the game has any glaring flaws, it’s that its ideas are quite literally too big for the system it’s confined to. The Game Boy Advance’s screen clocked in at 240 x 160 pixels, or 5.7 x 3.2 inches–considerably less real estate than the Genesis, which displayed at a resolution of 320 x 224 pixels. Take into account Advance 2’s breakneck pace, and the criticisms initially leveled at it—too hard, too unpredictable, too cheap—start making sense. Even with the game’s economical visual presentation (rendered, I might add, with absolutely stunning sprite work), the screen size is limiting. There are several instances where an enemy might come at you just slightly too fast, or you may not be able to make a jump without a bit of guesswork.

I acknowledge these shortcomings, but I also can’t help but respect the ambition that spawned them. The designers could have easily made the game slower. They could have eliminated boost mode altogether; the game plays fine without it. But they must have known, deep down, that the integrity of their ideas was far more important than a dinky piece of plastic. Advance 2 was the tinderbox for something new. Sonic Adventure reinvented Sonic in 3D, and this would reinvent it in 2D. Two parallel design paths, budding in tandem, each continuously fulfilling the medium’s most primeval purpose—to go fast—in fresh and exciting ways. God, imagine it. Wouldn’t it be great?

Frustratingly, this actually did happen, just not in any of the ways it should have. The following 2D and 3D Sonic titles—Sonic Advance 3 and Sonic Heroes, respectively—bore several hallmarks of their immediate predecessors, but were too encumbered with superfluous ideas to meaningfully build upon them. Going forward, things were generally messier on the 3D side of things, and still are. Sonic’s most recent 3D outing, the open-world Sonic Frontiers, is an admirably big swing, but it ultimately does little to justify itself.

The 2D entries were more promising, but still trended downward. SEGA’s handheld follow-up to Advance was Sonic Rush, also co-developed by Dimps. As much as I enjoy Rush, it was the death knell: the game was the first to implement a boost button, clearly aiming for the highs of Advance 2 but vitally misunderstanding what made that game’s boost system so appealing. Nearly every 2D (and later 3D) Sonic game since has featured this mechanic, and none have fully nailed it. Maybe it’s a dead-end design, or maybe Advance 2 just casts too long a shadow.

A bit of trivia, and then an anecdote. Advance 2 was the first side-scrolling Sonic game without a single water level. This is great, because water levels in Sonic games are terrible, molasses-slow misery gauntlets that grind like sandpaper against everything that makes the series fun. But there’s an additional wrinkle. The first stage of Advance 2, Leaf Forest Zone: Act 1, does actually contain two separate pools of water, both of which are fully explorable. Characters move more sluggishly underwater, and if they stay submerged for too long, they’ll drown—two mechanics dating back to the original Sonic the Hedgehog. These mechanics never once matter here, because water doesn’t show up anywhere else in the game, and the pools in Leaf Forest are small enough that players can exit them with ease (or even avoid them altogether). They are, perhaps, the most personal flourish in Advance 2. Vestiges of its early development, likely implemented before its creators had fully cracked the code on what a perfect Sonic game should look like. A reminder, however small, of their growth.

I’ve been playing Advance 2 since I was seven. I know I was seven, because the game launched in North America on my seventh birthday. I’d never played a Sonic game before, and at the time, it seemed endless. The stages were colossal, their mystique bolstered by the fact that seven “special rings”—which unlocked bonus content—were hidden inside each one. I played Advance 2 until I beat it, then I beat it with every character, then I combed through every level until I’d discovered all the secrets, then I did that with every character, and then I just kept playing it, repeatedly, with no particular goal in mind. (It’s a pristinely replayable game, less than 45 minutes if you’re hurrying, which you obviously should be.) Over time, largely through sheer practice, I learned everything about it: the layouts of its levels, the movesets of its characters, the intricacies of its movement. It became akin to a fidget toy, something I’d pick up whenever I wanted to occupy my hands. Eventually, I felt like I’d hit a plateau. The first game I’d ever loved had finally run out of things to show me.

Several years later, I found out about Sonic’s air dash.