After seven years, the haunting episodic adventure game Kentucky Route Zero is finally complete. The game’s first chapter came out on PC in 2013. Tomorrow’s Act V marks the end of the story. A new “TV Edition” for consoles collects all five acts—the main story pieces of the game—and four interludes—side content that ties back into the story. I’m mainly a PC gamer, so the thought that there is no longer more Kentucky Route Zero to expect is strange. But if you primarily play on consoles, it’s possible you’ve never played, or even heard of, Kentucky Route Zero before. You’re in for something special. It’s a game that reminds you that you can only do so much, but there will always be things—maybe too many, maybe not enough—left to do.

It’s hard to sum up what Kentucky Route Zero is. It’s a game with a misleadingly simple premise: you need to help a guy deliver some antiques. It has a similarly misleadingly simple aesthetic: the art is all blocky shapes and solid colors. Gameplay is simple, too. You mostly pick between text-based dialogue options. Sometimes, you drive a truck. Once, you drive a boat. The game, however, is anything but simple. It’s rich, deep and provocative. It’s crammed with places, characters, ideas, references, and themes, all of which feel like they’re trying to say something about everything.

I made a valiant effort to get that guy to make his delivery, at least in the very beginning. But then I forgot all about where we were trying to go and got swept up in all the other things the game is about: big business, and trash, and ghosts, and regret, and longing for lives you used to live or never got the chance to, and all the ways you can spend your time and also all the ways you can’t. Kentucky Route Zero is sad, but also hopeful—not the hope that things are going to be better, but the fact that things keep happening, so at least there’s always someone to meet or something to see, something to remember or something to let go.

Act V is the only new content in Kentucky Route Zero: TV Edition. If you’ve played the previous acts, it’s unlikely you’re here just to find out if you should play Act V, but: you should play it. I won’t spoil it for you, even with a screenshot. One of the most compelling things about Kentucky Route Zero is being surprised by something weird or beautiful. The opening moments of Act V get their impact from how different they are from the end of Act IV visually and emotionally. I don’t want to ruin them for you.

Act V took me about an hour to play. It’s tonally different from the four acts that precede it. The color palette is brighter. It’s a much larger ensemble than we’ve played up to this point. The gameplay has changed, too; in particular, where Kentucky Route Zero usually has you choosing between dialogue options, Act V also presents you with highlighted words embedded in the text, more like the way you’d play a hypertext game. As with all of Kentucky Route Zero, these choices can change the plot a little, but mostly they reveal different aspects of a situation. They shape a scene’s tone, or just give you information you don’t totally know what to do with but which feels nice to know. To the end, Kentucky Route Zero remains a game where you can’t really make a wrong choice, which helped me just enjoy the last stories Act V tells.

When I first got my Switch review code, I was tempted to jump straight into Act V, but I couldn’t bring myself to do it. On a practical level, I had a hard time remembering where I’d left off since Act IV came out in 2016. I’m glad I replayed the whole thing, and if you’re returning to the game, I’d advise you to do the same. I don’t think Act V would have had the same resonance if I hadn’t gone through the journey of the entire game to get there. I might have been disappointed about some of the questions it leaves unanswered, and it would have felt cluttered with characters I couldn’t remember. But having arrived at Act V after traveling with these people, either personally or second-hand, the end of the game felt right.

Let’s get the rest of the business out of the way: Kentucky Route Zero plays well on Switch. (I haven’t played it on Xbox or PS4.) The art translates well to the Switch’s small screen and scaled up fine when docked into my PC monitor. It’s had gamepad support for a while now on PC, so the controls are intuitive. On Switch, you can also use touch controls; when you touch the screen, you get the lovely interaction of placing a virtual horseshoe that swings around a post and draws your character to it. I only struggled a few times to get a character to navigate to the right place without using touch. I’ve always considered Kentucky Route Zero to be quintessentially a PC game, especially given its roots in point-and-click adventures, but it makes sense on Switch. It was nice to carry around with me, picking it up and putting it down as I would a good book.

If you’re completely new to the game, let’s back up a bit.

Kentucky Route Zero was first announced via a Kickstarter trailer in 2011, and Act I came out in 2013. Since then, the rest of the acts have dribbled out in 2013, 2014, 2016, and now 2020, along with free interludes that brought in new characters and mechanics. The developers, a three-person team called Cardboard Computer, told me in an interview last week that they initially thought the game would be fairly small and take a few years to finish releasing. Things grew in scope as they worked. They found new ideas to explore, programming tools got updates that required overhauls, and they struggled to find a sustainable pace for such a small team. “To us internally we made like 10 games,” developer Tamas Kemenczy told me. In particular, making Act II changed their schedule, as Kemenczy developed a repetitive stress injury from programming that inspired the team to rethink their pace. “The only thing that really helped heal that and keep it under control,” Kemenczy said, “was… approaching a more reasonable schedule at a more human scale.” In some ways it feels like the game took forever, but as developer Jake Elliott said, “The pace has been one game every couple of years which is—when you think about a game studio who makes a new game every couple of years, that sounds pretty reasonable.”

Act I starts with a basic premise: Conway is an aging driver for a store called Lysette’s Antiques, and he can’t find his way to the address of his final delivery, 5 Dogwood Drive. He rolls into a gas station, Equus Oils, with a rumbling truck and an old dog in a sunhat, whom you can name Homer, Blue, or leave unnamed. Conway asks a blind man named Joseph for directions, and Joseph tells him he’ll have to take a road called the Zero to get there. He sends Conway to a woman named Weaver Marquez for help finding the road, along with a TV he wants to return to her.

The directions to Weaver’s place are weird—“Turn left as soon as you see that ugly tree that’s always on fire”—and things get weirder from there. Weaver speaks enigmatically, and also the TV is broken, so now Conway has to go find Weaver’s cousin, Shannon, who can fix it. Shannon is skulking around an abandoned mine that has a tragic history, and she tells Conway that Weaver sent her there to find “something I’ve been looking for.” Conway and Shannon explore the mine, during which his leg is injured by falling rock. When they go back to find Weaver, she’s gone, but it’s also possible she was never there to begin with. At the end of Act I, Shannon and Conway find the Zero by tuning the static on the old TV, revealing, as you explore in Act II, a strange circular highway with weird place-named like “the bat feeder” and “the anchor.” Everyone Conway and Shannon meet along the Zero has some basic goal—get to a music gig, deliver some mail—but they’re more than happy to help Conway with his delivery. You guide various characters or the whole group on their rambling attempt to finally get the stuff in that truck to 5 Dogwood Drive.

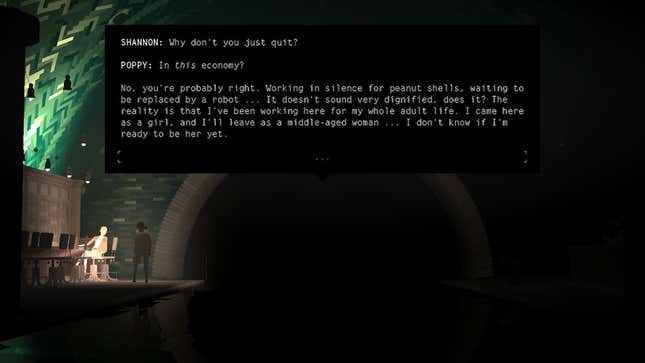

The delivery is largely secondary, and I often forgot all about it while I played. Mostly you drive around while strange characters talk about their strange lives. The player steers a vehicle along the map, or explores scenes and picks between dialogue options. A lot of the people who get mentioned by someone show up eventually, taking your wandering in new directions. Everyone talks like they’re thinking aloud, and some of the places where you find them might not even be real. Kentucky Route Zero is magical realism in the sense that there’s weird stuff like ghosts and giant eagles and a floor of a bureaucratic office populated by bears. But the game never asks you to figure out what’s “really” going on.

The plot, like the Zero, is hard to navigate, but it’s much more fun to just go where it takes you. You’ll miss things, depending on where you drive or which dialogue options you pick, but I never felt like I’d picked the wrong choice. Kentucky Route Zero doesn’t feel like the kind of game you have to replay to fully understand, though you might want to. Act III took me the longest, as I explored the Zero and the surface roads looking for landmarks. Some are marked in the game’s menu, in a notebook called “ephemera,” while others you come across as you explore.

Kentucky Route Zero has a unique brand of FOMO. There’s so much lurking around that you’ll never really know if you’ve seen it all, which can be maddening. It also fits the tone of the game, where you did some things and not other things because that’s how life is. I replayed Act IV from beginning to end twice, purposefully picking the options that hadn’t called to me the first time: send child companion Ezra with tugboat pilot Cate to collect mushrooms (oh, right: in Act IV you’re not in your truck on the Zero anymore, you’re on a tugboat on the Echo River, because apparently you have to get to Dogwood Drive via boat now), going to make phone calls with the crew, teaching your friends a card game. I was surprised by what a different experience Act IV was when I picked the choices that didn’t come naturally to me, but one playthrough didn’t feel more “correct” or less satisfying than the other.

Kentucky Route Zero explores what people do or don’t do with themselves, and how they remember their time after they’ve spent it. In a late Act IV scene, two characters recount a seminal moment in their lives differently. Restaurant cook Ida remembers her husband Sam indulging in malt liquor and sudoku on the night that saved their business, while Sam remembers drinking coffee while doing a crossword. They remember the big outcome differently too: Ida was inspired to come up with new dishes, while Sam found new places along the Echo River to catch fish. In another game, this might lead to an argument, or the player might wonder which version is “true.” In Kentucky Route Zero, both versions are true. All the things you might see in a playthrough happened, and so did all the things you didn’t. There are a few instances where the game takes you to plot-essential things you missed, but more often someone mentions something unfamiliar as if it’s obvious, or a character appears who acts like you’ve met them even if, in your playthrough, you haven’t. This can give things a sense of vague familiarity, and sometimes a strangely sweet regret. It can feel like lying in bed thinking about an old ex or a job you could have had—Kentucky Route Zero’s weird situations can be hard to relate to, but the emotions it evokes aren’t.

If you couldn’t tell by now, there is a lot in the game. Much ink has been spilled on its references and inspirations from film, literature, history, gaming, and technology. In our interview, the developers told me these references aren’t vital for understanding the game, with developer Jake Elliott saying they’re “almost like built-in footnotes.” This time around, a lot of the game’s dialogue reminded me of the short stories of Raymond Carver, but this merely served to remind me how much I like Carver’s writing, which was a nice thing to remember. It’s how I think the game wants you to feel about many of its references: these are things in the world you’ve chosen to pay attention to. All these references could seem pretentious, which might make you feel smart or which might make you feel stupid. A lot of them, as well as the game’s poetic dialogue and meandering plot, sometimes veer into what felt to me like nonsense. (“There’s some nonsense in there for sure. Nonsense is interesting,” Elliott said when I suggested this in our interview.) Personally, I have a hugely low tolerance for nonsense, so it’s surprising how much, if not all, of Kentucky Route Zero’s nonsense I’m willing to tolerate.

The references and themes and poetic flights feel purposeful, like the game is intentionally cluttered to inspire you to think about clutter. Junk and trash are a recurring motif, beginning with the antiques Conway is supposed to deliver, which are basically expensive trash someone couldn’t bear to part with but then had to. There are eddies of garbage along Act IV’s Echo River. In the Bureau of Reclaimed Spaces, you can find hermit crabs wearing shells made out of paper clips and printer cartridges (you can also, of course, miss the crabs entirely). Obsolete technology is everywhere. It’s all the stuff people can’t get rid of or make work: moldy computers and a failing public access television station and the TV Shannon has to fix to get you to the Zero.

There are several big companies in the game that use people up and discard them. The Hard Times distillery and its malevolent “boys,” with whom Conway gets tangled up due to a drinking problem and some debt that’s financial, but also emotional. There’s the Consolidated Power Company, a monolith that has its hands in everything from Conway’s leg to Act I’s mine tragedy to the first task you have to do in the game, flipping the breaker at Equus Oils.

These companies and their actions turn people into ghosts—actual ghosts, which Kentucky Route Zero has a lot of—and more metaphorical ones, people haunting the places that used to exist or the lives they used to live, just persisting, because things do. Ghostly musicians drift in and out, playing beautiful gospel tunes. There’s the ghosts of the half-familiar mention of an event the player didn’t experience or a character they should know. Or there’s a reference that will make you think of a play you might have seen. Or perhaps there’s an allusion to a book you think you’ve read.

When Kentucky Route Zero first appeared, I wanted to write about games but I didn’t much. I was a freelance editor who ran an impactful but pretty broke publishing company. I knew a lot of people I don’t know anymore: some of them moved away, and some of them died, some I made leave, and some stopped wanting to be around. I’m shocked by how different my life is now from when the first act came out. Parts of it remind me of who and where I was when I first played them, and it’s hard not to look at the game as a whole without also remembering that stuff.

Right now it’s the morning, and I’m rushing to get a draft to my editor, achingly aware of all the other things I have to do today and the demands editing it will now put on his time. I’m on my couch at home, and it’s the time of day when the sun creeps across my east-facing windows and makes it hard to see my computer for a while, so I keep moving around on the couch instead of just closing the curtains. This always happens at about this time, and I never close the curtains. I’ve never actually associated this minor annoyance with a time on the clock. It’s just “that time when the sun makes it hard to see,” a time unique to where I’m sitting in the apartment I live in. One day I’ll probably live in a new apartment, and I won’t even remember the thing with the sun unless this part of the review stays in the final version, and I remember having written this one day, and I read it again. That’s a lot of “if”s.

The next person who lives in my apartment will mark their time in a completely different way that I’ll never know about, as they go about a life that will intersect with mine only because we paid our money to the same landlord so we could pretend we owned the same cluster of rooms that really belong to a guy much richer than us. I’ll haunt the people who live in my temporary home the same way the past tenants haunt me, through a badly-hung mirror or wondering how they dealt with the light. None of that is very important, but it’s happening now and one day it won’t happen anymore. That’s just how life works. It’s cool how some people managed to cram some of it into a video game.