71-year-old Japanese artist Yoshitaka Amano—best known in gaming circles for the Final Fantasy concept art he’s made for developer Square Enix since 1987—is having a great weekend. Before I sit down with him at New York’s Japan Society, which was screening his film collaboration Angel’s Egg (1985) that night, he had already attended his latest gallery opening, retrospective The Birth of Myth, at Lomex in Lower Manhattan. On Instagram, I saw him get flocked by teen girls throwing up depressed peace signs in their selfies, but in which he seemed impassive.

Across from me now, he’s still congenially nonchalant while wearing a Death Row Records t-shirt.

“Monchhichi,” he says while I settle down, reaching out of his chair to point at the cartoon monkey head that dangles from my tote bag. I flip it around to show him that it holds my driver’s license, too.

“Sugoi,” he agrees.

We communicate through Amano’s translator for the rest of our conversation while, downstairs, fans pack Japan Society’s lobby. Some people had been lining up for the 6 p.m. screening since 3:30 p.m., communications manager Kazuho Yamamoto informed me. Audience members later recognized Brooklyn indie music legend Caroline Polachek sitting near the front row.

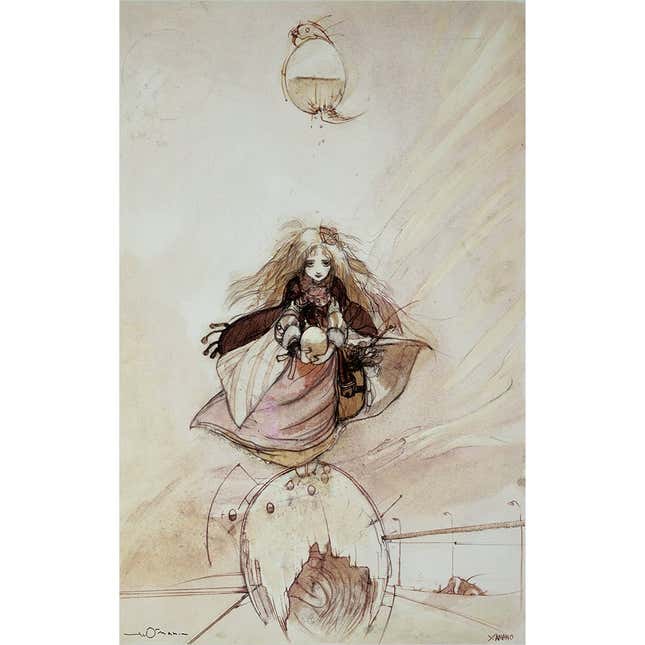

I don’t know if everyone there is more obsessed with the science fiction of Amano’s art, which is languid with women, sharp buildings, and monsters, or the rarity of watching straight-to-VHS Angel’s Egg in a crowd. The film was a commercial flop, or a hallucination with barely any dialogue, loosely about a child who hides a perfect egg under her petticoat until it breaks. Seeing it in company is a novelty. Or maybe they’re taken with impenetrable Amano himself, though, in our interview, he doesn’t shy from the fact that he’s just a man.

The first time I saw the melancholy Angel’s Egg, which U.S. anime fans retroactively decided was a surreal masterpiece, I fixated on the protagonist’s hair—when she runs from a sulky guy preoccupied by her egg, it fans into individual strands, tracking her like a sheet of rain.

Though he can’t recall the last time he even watched Angel’s Egg (it was “maybe ten years, maybe 30 years,” he says during a Q&A later that night), he recognizes his “essence [...] in there.” Amano knows he created 300 total illustrations for the movie, including those with all the pieced-apart strands of hair. He’d make up to 20 drawings a day, prompting him to sleep on the floor of the studio. It’s a lot of work to put into one little girl.

Amano agrees with my assessment that he’s drawn to feminine energy. In fact, he previously noted in a 2012 Kotaku interview that his ideal project was “something with cute girls,” he told Jason Schreier. He’s a man, he reminds me. Women are attractive.

“In my free time, [...] I naturally draw female characters,” he says, referencing his pastel-colored, doll-eyed Candy Girl series and penchant for drawing angels. “I think, as a male, we know who we are, but women are more mysterious.” He laughs. “It’s really complicated and hard work.”

Less predictably, Amano expressed surprise at Angel’s Egg’s cult-classic status. It had a disastrous initial launch, he later said at the Q&A, and informed me that director Mamoru Oshii (also known for Ghost in the Shell) lost the job he had lined up after it.

“He wasn’t able to get a job for a while,” Amano told me. The gaming industry is like that, too, he adds. “If it doesn’t hit [immediately], you’re not allowed to make more.”

But, in the ‘80s, Amano was fatigued by his animation job at Speed Racer studio Tatsunoko Productions, where he began working at age 15. Angel’s Egg might have bombed, but it was different, and Amano and Oshii were proud that they made “one great project.”

Amano finds the movie’s emotional success with audiences more satisfying than sales numbers. He is, I guess, concerned with the internal. Despite collaborations with Vogue Italia, and, more recently, made-to-order New York couture brand Vestium, he doesn’t think external trends like fashion affect his work, and he’s totally uninterested in AI-generated “art.”

“It doesn’t really pertain to me,” he says. “I just love drawing pictures. [...] For AI, you have to [...] feed in information, and then it creates something for you. For example,” he says, picking up the shimmering black hat he’d been wearing around New York. “As a person, you can throw the hat if you want to,” he tosses it across the table and drags it back, “but AI wouldn’t just do that. Maybe in the future, there’s data where [it would], but humans have to make that action. As a human, you do it, and you’re enjoying it.”

He’s more interested in “daily life” thrums, he says, and he tends to blend street fashion with his own visions. He similarly denies his art being influenced by politics, though, in 2019, he designed a campaign with Japan’s dominant nationalist Liberal Democratic Party. It depicted seven politicians, including former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, who denied much of Japan’s bloody imperialist history, as windswept samurai.

I ask him if he thinks artists have any social responsibility, and he speaks generally.

“More than social responsibility,” Amano says, “there’s human responsibility.” Don’t bother people, don’t cause trouble, stuff like that. “We all have [that responsibility]. Not just myself, but everybody.”

He doesn’t think any more of it, and I don’t press further. He’s taciturn—after the Angel’s Egg screening, “Uhhh…” was all he said to the sold-out theater’s impassioned round of applause. I sense that, despite his fans’ tendency towards romance (“What’s your relationship to dreams?” Polachek asked during the Q&A), Amano can be superficial. He’s a man, and he draws. Yes, that’s it.

“If people don’t understand my work, maybe it’s my fault,” he says. “My responsibility is the creation and completing it [...] and then, once it’s out of my hands, everyone views it, and I can’t control that.”

All that matters to him with his work is constructing “a world that people have never seen before,” he says. “That’s my vision, my goal.”

Angel’s Egg’s New York screening is appropriate, then. Amano considers New York to be a “fantasy city,” an opinion he first formed while living here in the ‘90s. There was “a different feeling to the city” then, he said. “You don’t really know about a city until you visit again in person. The smell [changes], or there’s new buildings.”

Soon, Amano will return to Japan, where he’ll start working on illustrations for a new game. “I feel like art equals gaming,” he says, “In a sense, they’re one and the same in my eyes.”

Like many in the gemstone-shaded eyes of Amano’s art, I can sense opportunity—what game? Amano speaks in English for the first time during the interview: “No comment.”

But, “I think it’s a game that everyone will know,” he says impishly through his translator. “Sorry. Sorry, I cannot say. [...] Art, of course you can talk about it. But—”

“Gaming is secret,” I supply.

“Secret, yes.”

*