Crusader Kings the video game is a massive, unwieldy thing that can’t possibly be crammed into a 2-3 hour board game experience. But developers Free League, bless them, have certainly given it a shot.

Crusader Kings the board game tries to take pretty much every key element of Paradox’s grand strategy series—dynastic characters, complex diplomacy, unrest, crusading and a general sense of cruelty and dread—and work it into a tabletop experience for 2-5 players.

It does a pretty good job, but after a few games of it I’ve come to the conclusion that it might have been better if instead of trying to adapt the whole video game, they’d just focused on the bits that work best in the flesh, sitting in front of a table.

Crusader Kings has you playing not as a nation but as a ruling medieval family. Players choose from one of five broad ethnic regions—English, French, Spanish, Italian and German—and then spend three eras securing their dynasty’s place in history by taking territory, going on crusade, securing alliances and safeguarding the future of your throne by producing heirs, with every character in the game having their own distinct personality defined by various traits.

That last bit is often both the most important (and satisfying) part of the video game, as you match princes and princesses from across Europe with suitable partners, and it works surprisingly well here. It’s drastically scaled back, of course, with Kings having only four personality traits and everyone else just one. Your own family’s new births, and other inhabitants of the game (there are realms initially outside the human player’s control) are faces drawn from decks of cards, who are then randomly assigned traits from a big bag of tokens saying stuff like “weak” and “pious.”

So every competing dynasty has its own distinct family that evolves over time, and is different every single time you play. And when that family grows old and eventually dies (the game roughly simulates the passing of time), you take them off the board, slide their children up into the positions of rulers and the cycle begins anew.

The traits aren’t just for fun, they serve a couple of important purposes. Firstly, they directly relate to many of the actions and events taking place in the game; devious Kings are more likely to be able to pull off treacherous moves. But they also replace dice, and to resolve the game’s numerous checks you have to dip into a bag containing all your family’s traits instead of rolling for a hit.

You’ll usually start with two “good” traits and two “bad” ones, and as the game goes on, stuff happens and your lineage expands, you’ll add more and more traits to a rather luxurious felt pouch that comes with Crusader Kings. When performing a check you’ll usually pass if you draw a green trait, and fail if you pull out a red one.

Cultivating your family’s traits, then, is just as important here as it is in the video game, and adds a strategic layer to many of the game’s seemingly straightforward choices. While it’s easy to marry one of your kids off to the ruler of a nearby independent realm, if their future spouse has a “bad” trait, it’ll be added to your bag later on in the game, increasing your chances of failing checks.

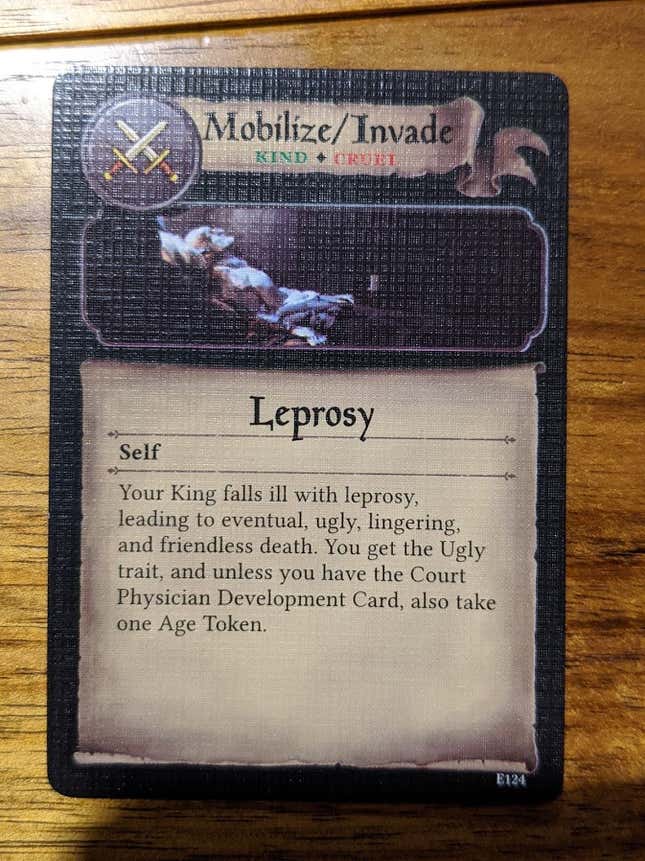

Crusader Kings’ gameplay is powered by decks of action cards, each responsible for the game’s possible moves each turn, like going on crusade, waging wars with neighbors, improving your realm and collecting taxes. You draw eight cards per round, but only play six, giving you a slight bit of hand management in case of some patchy luck. Each card is divided into two sections: Up top is an action that you directly perform, whether it be building a castle or mobilizing your forces, while below is an effect, which can sometimes be beneficial, sometimes quite plain and sometimes absolutely disastrous.

Dynasties play two cards per turn, there are three turns per round, and then three rounds per era, or which are are three. Slightly confusing, I know, but that’s how the game has built in the passage of time, as at the end of each round each player has to add an age token to their King or Queen, and once they hit five, they die of old age (they can, of course, die earlier, through event cards, going on crusade or even being assassinated by other players).

Crusader Kings’ scoring is very simple. You get a victory point for every region on the map you control, you get a victory point for holding one of a handful of achievement tokens (given out for things like being the first player to build three castles) and in case of a tie the winner is resolved by whoever went on more crusades. That’s it. Everything in the game boils down, for the most part, to who’s holding the most land.

And this is where things start to fall apart a little. Crusader Kings the video game isn’t about “painting the map” with your empire at all. Sure, it’s possible, but it’s a game about political intrigue and diplomatic cunning above all else, and it’s as fun playing as a tiny Welsh Dukedom, meddling in the affairs of the local elite, as it is ruling over Europe as the Holy Roman Emperor.

The board game doesn’t give you that scope. It’s conquer or nothing, which makes a lot of the game’s best elements—like building a family tree and haggling with rivals—feel a little pointless. If expanding your realm is basically the only viable path to victory, a lot of the game’s systems that allow for intrigue and management fall by the wayside.

Making matters worse is that Crusader Kings’ design is so tilted against going to war with other players that you’d think its creators were intentionally trying to keep things peaceful, working against the expansionist brief of the victory conditions. Despite the game board looking like its full of military units ready to roll into neighboring realms at a moment’s notice, going to war in Crusader Kings is a slow and torturous process that’s rarely worth the hassle.

Before you can attack another dynasty you first need to mobilize an army, which costs you a card. You also need to formulate unrest in that realm, which again, costs you a card. Then to actually invade you need to play a card. Oh, and before you do any of that, you need a Casus Belli first. And then the person you’re attacking likely has allies, since marrying off your kids among your rivals is such a necessary part of the game.

This is pretty similar to the laborious process involved in going to war in the video game, but that’s designed to be played over dozens of hours. The Crusader Kings board game is trying to keep things capped at 2-3 hours, which makes your limited amount of turns precious. Blowing multiple cards preparing then going to war just isn’t worth it when you can only hold a maximum of eight territories anyway, and there are plenty of nearby independent realms to conquer instead.

Warfare isn’t the only place Crusader Kings’ time constraints work against an otherwise fun system. The building and management of your family tree is so cool. It’s probably the best part of the whole game, and seeing sons and daughters traded across the board, securing alliances and potentially the future of your dynasty, is immensely enjoyable. But the way time works in Crusader Kings means that most games will see you only go through a couple of Kings, sapping the system of much of its potential.

There’s a lot to like about Crusader Kings. I love the fact it’s competitive without being overly hostile, and there’s just the right amount of horse-trading to keep everyone busy in everyone else’s business, making it a great social experience.

But I’m ultimately frustrated and let down by it as well. While I admire the attempt at adapting such a sprawling digital experience into something remotely approachable (and even teachable to casual players, unlike Paradox’s game), Free League might have bitten off more than they could chew here.